My first screening proper of the 68th Berlinale, and I’m sat behind a middle-aged hetero couple. The guy falls asleep ten minutes into the three-film programme. The woman spends more time looking over at him than at the screen. When the lights come up and the film-makers are introduced for the Q&A, she starts taking iPhone photos of the auditorium’s ceiling. When she’s done he starts doing the same. (It was an unremarkable ceiling to my eyes.) Before the end of the first director’s first Q&A answer, they leave.

People suck; their loss. They missed a great Q&A with Deborah Stratman, who to my mind is one of the century’s major-major filmmakers, and also a genius at making non-explanations of her work utterly compelling. Her new one Optimism is showing for the first time in the festival’s Forum Expanded section, it’s a quarter of an hour long and I can’t quite shake its bright, grainy loveliness. It’s a miniature study of a town in Canada’s far-north which was built on a gold rush, which Stratman initially visited for a joint sculptural project with her husband. But she grew fascinated with the warmth of the town’s spirit, the uncanny energy of this tight community founded on mineral wealth. Some of that project’s light sculptures appear in the film, used almost as visual punctuation; a shining mirrored ball appears at different points, cut among some of the most ethnographic scenes I’ve seen from her. These moments of eerie beauty peppered in this tender, joyous town portrait are emblematic of Stratman films’ best quality, how they slyly weave disparate threads not to construct arguments but to sculpt ideas.

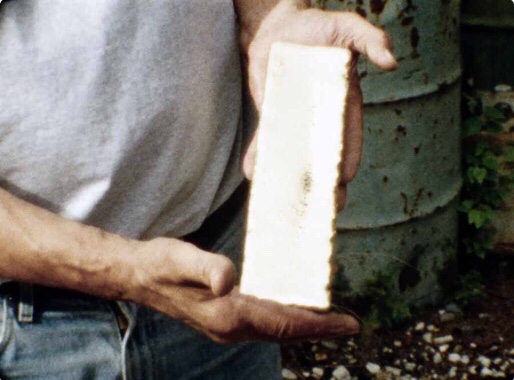

In this town formed on gold, we eventually meet its miners. Some of the images of blocks of gold being sculpted and set aflame feel like they’ve been seared into my brain – I’m a total cheerleader for digital, but these Super-8 images pop. While she was filming, the price of gold shot up again, causing the town’s inhabitants to feel as if their community would become mega-rich again. In the scenes which feature the delicate process of gold treatment, the score of Chaplin’s The Gold Rush is placed into the soundtrack. It’s very funny, in a meta-mischievous sort of way, and the audience laughter in these moments attest to Stratman’s awe-inspiring command of her viewers.

As I often am, I’m reminded of Village silenced, an experiment in cinematic appropriation she made pre-Illinois Parables. It’s a three-minute study in sound and historical notions of control in which Stratman re-works images from Humphrey Jennings’ WWII propaganda film, The Silent Village, itself a startling proto-Twilight Zone nightmare depicting a fascist invasion in a romanticised South Wales Valleys community. The longer I linger on Village silenced, the more I think of it as a major shift in the way I think about sound in cinema and in the twenty-first century. All she does is alter parts of the Jennings film’s soundtrack, but it’s suggestive in a billion different ways, terrifying and provocative and brutal. Sound is less obviously foregrounded in Optimism, but is arguably equally integral to the work.

(By the way, if anyone reading this is in Berlin or knows someone who is, be sure to get a copy of the little Forum Expanded catalogue, which contains a bunch of Guy Maddin illustrations and a few great pieces from Forum’s returning filmmakers on what they’ve done since their last time in Berlin and how they feel to be back. Stratman’s is one of the best: “It’s good to watch films shot in places I don’t know, in a city I don’t belong to. I like the stack of disorientation. But cinema orients me too.”)

I saw Optimism in the fourth of Forum Expanded’s screening programmes, which are separate from the section’s main exhibition space but curated alongside. Its two accompanying films, though longer, paled in relation to Stratman’s film in rigor, originality and visual appeal. They were grouped together for their complementary thematic approaches towards excavation as physical labour, as metaphor and as gateway into micro and macro histories. It goes without saying that all three are thus also films about the processes of their own creation, about image-construction as archive, essay as archaeology. Stratman mentioned after the screening how Optimism somewhat accidentally became a film about cinema’s relationship to things which will inevitably outlive it (rocks, minerals, mountains). She shot it, she said, on a Super-8 camera clothed in a little winter coat, the only camera that could weather the snowy conditions.

In the Ruins of Baalbeck Studios turns an exploration of a fascinating chapter of Arab film history into a dully fetishistic polemic about celluloid and preservation. Its director, Siska, has apparently been celebrated as a (former?) graffiti artist, and claimed to cry every time he sees the film. I’ll just say that his Q&A answers did little to convince me of the film’s artistic merit, although they did give us the amazing description of contemporary Lebanese politics as “a big bucket of political salad.”

Jan Peter Hammer’s Dug, the third film in the programme, was… fine. Again, an interesting history, conceptually a little stiff, all around a little uninspiring. And if you’re going to lean that much on on-screen text as your expository strategy, the least you can do is opt for a less ugly font.

Though I’m glad I saw it on a big screen, in a near-full-capacity audience, I wish I could revisit Optimism like I did a few Expanded exhibition favourites. With Strange Meetings, Danish-Korean artist Jane Jin Kaisen uses various documentary media to essay a site in South Korea where a U.S. military STD treatment centre once sat. Its video component starts off as a forensic exploration of the decomposing site, its dusty corners and empty window-frames, all slow pans and lingering close-ups. Pairing the video with archival materials from the treatment centre lends the work a historical integrity, but the work gleefully eschews oppressive seriousness. The pamphlets, postcards and letters shown are a little surreal and sometimes darkly funny. FIGHT… syphillis and gonorrhea; He “PICKED UP” more than a girl…; Make our men as fit as our machines! Maybe I have a strange sense of humour. These old warnings are placed alongside more recent documents referencing the resurfacing of the political legacy of Korean comfort women.

It’s unexpected, considering the loadedness of its setting, that Strange Meetings was the most purely life-affirming work featured in the Expanded exhibition. After a few minutes of studious buildup, the video pans to a thin crowd assembled outside the building. The bulk of the video then focuses on a performance which takes place on the disused site every weekend, in which a cross-dressed, garishly face-painted man dances, plays drums, sings and breathes fire to a rapt audience of locals. It’s pretty nuts.

I returned to the work a few times. Its images are electric and confounding and kind of joyous, and most of that joy, I think comes from Strange Meetings‘ refusal of didacticism. We are invited to think about bodies, and contamination, and movement, and how all those things interact with military-industrial, neo-colonial, geo-sexual memory – I guess – but it’s such a generous, slyly impactful work that really it was most pleasing just as a sensory experience, images to look at and find pleasure in. In this sense it’s of a piece with the Stratman film. Here are two filmmakers who know restraint, who know that muscular images and an intelligently conceived starting point are often all you need. What a pleasure (almost disconcerting!) to see a work in this kind of setting that feels both intellectually satisfying and alive.

Sanghee Song Come Back Alive Baby satisfies a similar desire, but is even barer and simpler and more purely driven by suggestion than Stratman’s and Kaisen’s new works. It’s a three-channel installation which adapts the ancient Korean folktale of the Mighty Baby, in which an infant from a poor family is repeatedly killed and keeps resurrecting. The images we see, however, form an abstract collage of desolation, contamination and catastrophe, including footage from Chernobyl, various famines, natural disasters. They’re cut amongst each other so as to be basically incomprehensible on a linear level, but they’re fascinating to watch. I don’t know if it’s a coincidence or not that my standouts from the Expanded exhibition have a non-video component, in this case a cabinet displaying seemingly comprehensive reference sheets for the sources and sites included in the work, almost like a shot-list. In a less clever filmmaker’s hands, such a diagrammatic accompaniment would rob the work of some of its richness, but like I said, its register is so purely suggestive and its rhythm so seemingly instinctive that it adds to the work.

I’ve seen Come Back Alive Baby described as “apocalyptic,” a descriptor which feels a little unimaginative. Its basic materials are dark, but I’d hesitate to call Song’s synthesis of them pessimistic. It’s an inquisition into regeneration, myth-making and survival – even narrative itself – which gets the mind racing. Its shifting and transposing of registers and media never comes off as restless or ill-managed; every layer and micro-history introduced in the work adds a mystery rather than a frustration. You come out of it (and into The Otolith Group’s The Third Part of the Third Measure, which closes the exhibition like a tonic, which I hope to write about on here another time) with the sensation of having seen something pretty revelatory, even if you’re not sure how or why.

Come Back Alive Baby is about as joyful as its title suggests. But a few minutes into my first sit-down with it I had one of those film-viewing moments which are so totally mundane but so memorable in a very specific way as to seem something like a moment of transcendence. A real-life baby (with a hot dad!) crawled from its mother’s arms across the dark room towards one of the screens playing Song’s film. The baby tries to reach up and touch the screen, which is playing images of nuclear-decimated land while subtitles narrate the legend of the infinitely resurrected baby. The baby’s there for maybe three seconds before its mother goes to collect it.

And I found it incredibly touching, for some reason. It was a nothing moment that seemed to capture something very something. A lighthearted moment of relief for everyone in the room which opened up new ways of thinking, maybe. I like to think I’m approaching this Berlinale a little like that baby, absorbant and wide-eyed, trying to go up to the screen and touch it, to go into films with all the naive curiosity of an infant. I wonder if that might be something similar to the “stack of disorientation” Stratman talked about in her catalogue feature. Anyway. Films are good sometimes. As you were. x